The pandemic has made stress and anxiety familiar terms for just about everyone. But what does a true case of burnout look like?

Part of the problem with the burnout conversation is that we often misapply the word, or use it too loosely. The World Health Organization has updated its definition to clarify that this is something that happens within the context of work. Put simply, burnout is the manifestation of chronic workplace stress.

Everyone has everyday work and life stressors to deal with, and this stress exists on a continuum. One way to know if you are moving out of the stress zone into something that looks like burnout is to understand the three dimensions of burnout. The first is chronic physical and emotional exhaustion. We often just stop right there in defining burnout, and as a result, we misapply self-care and stress-management strategies to tackle exhaustion. But there is more to it. Burnout also entails a sense of chronic cynicism. People start to bug you, particularly your clients or the people you are called upon to work with, serve or help. All of a sudden their calls come in and you think to yourself, ‘Do we really have to have this call? Can’t you figure this out on your own?’

The third dimension of burnout is a sense of lost impact and disengagement from your work that leads to a ‘Why bother? Who cares?’ mentality. If we just have a bad day, sometimes we’ll say, ‘Ugh! I’m so burned out!’, but in reality we are not using the term correctly unless all three elements are present.

What are the root causes of burnout?

A simple formula is ‘Too many job demands and too few resources’. Job demands are all of the things that require consistent effort and energy, and you could probably list 25 of them pretty quickly. Job resources are the aspects of your work that are more motivational and energy giving in nature. The research points to a core five that leaders, teams and individuals really need to pay attention to as potential drivers of burnout.

The first driver is a lack of autonomy, meaning you have little choice or say in how your day unfolds. You can’t say Yes or No to projects, you have little decision-making discretions, high workload and high pressure, and often there is not enough staffing. This is the single biggest driver for burnout.

The second driver is a lack of support from leaders and colleagues. Basically, you’re in an environment where you just don’t feel supported. Perceived unfairness is a third driver. If you’re in an environment that lacks transparency, where there is arbitrary decision-making or favouritism going on, that is an important job demand to pay attention to.

The fourth driver is a values-disconnect. This is what leads people to think to themselves, ‘I expect certain things from my workplace, and my organization just isn’t providing them.’ The fifth one is something I see quite often, and that is a lack of recognition. People report that they are not being thanked for their work. Nobody is noticing that they’ve put in extra time or gone the extra mile, and that really starts to wear people down.

Teams that debrief on a regular basis

experience less burnout.

You believe the solution to burnout is systems based. How so?

When I first started looking into burnout (after experiencing it myself), I was focused on, ‘What did I do wrong? What could I have done differently?’ But the research is clear — and is backed up by my own conversations with people who have burned out: The environment in which you work is a big driver and influencer of whether or not burnout occurs.

Of course, walking into an organization and saying, “You have to fix your culture” is not going to work; changing an entire culture is very slow and expensive. So, where do we need to look within organizational systems to gain traction on dealing with this issue?

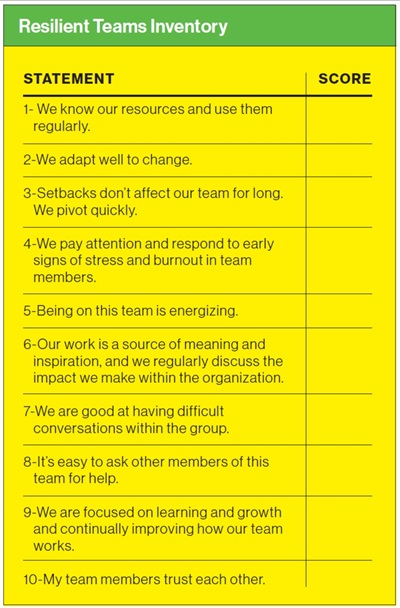

In my experience, that entry point is teams. I think of teams as mini cultures within the broader organizational culture. If you focus on teams, you can talk very directly to individual contributors and leaders and prescribe strategies that will help fortify the team. For me, this became a sweet spot to hit lots of different constituencies within the organizational system and start to tackle this issue in a systemic way with holistic strategies.

You have said that many of the tools and frameworks required to prevent burnout are ‘tiny noticeable things’ (TNTs). Please explain.

One simple thing teams can start doing right away is to embrace the practice of debriefing. You can do this at different points within the time frame of a project, a deal or whatever you’re working on. At pivotal points in the project, and especially at the end, simply come together to reflect and ask, ‘What were we intending to do here? Did we achieve our goals? Which aspects went well, and what could we change going forward?’

| 3 Warning Signs of Burnout |

|

Exhaustion. This happens when you are physically and emotionally drained. Eventually, chronic exhaustion leads people to disconnect or distance themselves emotionally and cognitively from their work, as a way to cope with the overload.

Cynicism. Everyone — from colleagues to patients to clients — starts to bother you. You start to distance yourself from these people by actively ignoring the qualities that make them unique and engaging, and the result is less empathy.

Inefficacy. This is the ‘Why Bother? Who Cares?’ mentality that appears as you struggle to identify important resources and as it becomes more difficult to feel a sense of accomplishment and impact in your work.

|

My research suggests that even taking 12 to 15 minutes is enough to increase team cohesion. Teams that debrief on a regular basis experience less burnout, because people leave the session feeling supported and they know where they stand. When there is a sense of transparency and people understand the role they are playing within a project — including what they are doing well and what they could do differently — that is enormously beneficial for us, and it leads to increased motivation.

Another simple TNT that individuals can focus on to avoid burnout is something I call ‘the 20 per cent rule.’ This came out of a fascinating study that looked at a group of physicians. They were asked, ‘What is the most meaningful aspect of your work?’ Then, they were encouraged to build in more time during their days and weeks to focus on those aspects of their work. The study showed that the physicians who spent up to 20 per cent of their time on the things that gave them the most meaning experienced half the rate of burnout.

Reaching out to a colleague to show concern

is almost always well received.

This requires being very intentional and asking yourself, ‘Could I start every work day with an hour of something that I find really meaningful?’ Being intentional about how you start or end your day can help you build little moments that add up over time in terms of morale.

Describe the role of ‘psychological safety’ in a resilient workplace.

This concept was developed by Harvard Business School Professor Amy Edmondson, and I include it as one of the two foundational pieces of my Teams Model (see Figure One). Psychological safety is essentially trust and transparency at the team level. It means people can say things and admit things freely, without fear of consequence. If your team doesn’t have this and it is not being cultivated intentionally by your leader and everyone on the team, it is going to be much harder to implement a lot of the other pieces of the puzzle. It will also make it harder for anyone to say, ‘Hey, I’m starting to have an issue with my stress level.’

Psychological safety is the puzzle piece that teams need to tackle first and foremost. Often, it is positioned as a leader-driven set of behaviours — and leaders do play an important role in cultivating psychological safety. But there are behaviours that everyone on the team can practice to continue to fortify that sense of openness and trust. It really requires ongoing practice. You don’t ‘get to’ a place of psychological safety one day and say, ‘Okay, we are done. We don’t have to worry about this anymore.’ It entails an ongoing set of trust-based behaviours.

| Leaders Beware: Burnout is Pervasive |

- 96 per cent of senior leaders report feeling burned out to some degree; one-third describe their burnout as extreme.

- Up to 50 per cent of physicians are experiencing burnout.

- A survey of teachers found that 87 per cent said the demands of their job are at least sometimes interfering with their family life. More than half reported they don’t have enough autonomy to do their job effectively, and only 14 per cent said they felt respected by their administration. Both of these factors drive burnout.

- In finance, 60 to 65 per cent of bankers aged 25 to 44 reported some level of burnout.

- In a study of burnout among lawyers, more than one-third of those surveyed scored above the 75th percentile on the burnout measure.

|

Talk a bit about how tools like appreciative inquiry contribute to resilience—and away from burnout.

I have been a fan of the concept of appreciative inquiry ever since I heard its originator, David Cooperrider, talk about it in my positive psychology class many years ago. If you want to make positive change for your mini culture (i.e. your team), you get together with them and ask a series of questions: What matters to us the most as a team? What is going right for us? What are some things we are doing really well, and how can we can leverage them to make our team even better? Every person on the team participates and gives an answer.

Then you think about what you want your team to grow into, and how you are going to get there. What are you aspiring to? What are some changes you are willing to make? Taking teams through this process is a fun exercise, because teams don’t often take the time to think about these things. I have found that it can be very, very powerful when you start to get people thinking in this way.

Another tool that can really move the needle is design thinking and the mindsets associated with it. Design thinking is a problem-solving process that involves empathy and being human-centred about the challenges faced by your team, as well as the challenges that your clients or colleagues are facing. As you are thinking about little tweaks or design changes to your team, you’re going to have to experiment and try things out. That is hard for a lot of folks, because we want to know the answer quickly. But, if you are going to change direction on something, you have to try little experiments. You have to pivot, and potentially ask for help, and then take all of that data and apply it to decide, ‘Is this the direction we need to go in?’

The lens through which I viewed my world narrowed.

It became just about work.

If readers feel they might be burning out——or have a colleague or family member who is——what do you suggest as a first step?

I get this question a lot. People wonder, ‘If I’m worried about someone, (a) should I say something, and (b) if I decide that I should, how do I approach it? The vast majority of people I have worked with — myself included — say they really appreciated that someone pulled them aside to let me know

that their stress level was not where it should be. Many people say to me, ‘I really wish somebody would have said something to me.’

I hope this encourages people to consider reaching out to a colleague, because it is almost always well received. At the very least, the person will take it to heart and think about it. Of course, this is predicated on making sure that you are the best person to be delivering the message. If you’re somebody’s

leader and you don’t feel like you have the right relationship with the person who you are concerned about, it should probably be someone else delivering the message.

But regardless, it’s a conversation that you need to be very intentional about. You need to go in with a clear understanding of what message you want to convey. You also need to make sure that you build in enough time to really ask the other person how they are doing and what’s going on, to get their perspective. It can be very tempting to jump to conclusions about what’s going on in somebody’s world but in reality, we usually don’t know the breadth of their situation, both at work and outside of work. We certainly carry outside-of-work stressors to work with us.

So, the short answer is, muster up the courage to say something. I’ve got a template in the book to help people walk through having a more informed and intentional conversation. My advice is, don’t wing it. It shouldn’t be, ‘ ‘Let’s take an additional five minutes at the end of this Zoom meeting and have this conversation.’ It has to be something that you build out enough time for.

You have described your own burnout as “a slow burn.” What were some of the early signs?

You don’t just wake up one day and go, ‘Whoa, I am totally burned out.’ It’s usually a process that happens over a period of time. Sometimes the initial signs are so subtle that we dismiss them as, ‘Oh, I’m just having a bad day’ or ‘I’m having a bad month.’ Or, we tell ourselves, ‘I’m just coming out of my busy season, and that’s why I’m feeling so cranky’. It’s important to pay attention to all of that and admit to yourself whether you are bouncing back toward your zone of optimal performance. If not, it is likely more than regular stress.

That was one of the first warning signs I had, because I wasn’t able to bounce back easily. I just stopped doing lots of things: I became totally focused on work and stopped hanging out with my friends as much. I even stopped playing co-ed softball, thinking, ‘I can’t afford to take that time in the evenings — I need to be focused on work and deal with other issues.’

That was a big mistake. The lens through which I viewed my world narrowed and became just about work. That is never a good thing. As exhaustion and cynicism started to creep in, I started coming in to work 10 minutes later, and I was saying No more frequently when colleagues asked me to go to lunch or out on a Friday after work. Anyone who knows me knows that is not my personality at all. But I was so tired, I just wanted to go home. It’s fine to do that every now and again, but it became a habit. Looking back on it, those were some of the initial things I noticed. Clearly, I got through it, and now my goal is to help others avoid the experience altogether.

Paula Davis is the founder and CEO of the Stress and Resilience Institute and author of Beating Burnout at Work: Why Teams Hold the Secret to Well- Being & Resilience (Wharton School Press, 2021). A former practising lawyer, she teaches resilience and leadership at Harvard Law School.

Share this article: