Let’s start with your book, The Conversation. How is it that conversation—something so seemingly simple that we do all the time—can be such an important part of addressing such a serious and complex topic?

Humans are not very good computers — we don’t just process data and information. People relate to people, and there are a lot of studies that show you can give people all the data in the world, but social relationships serve as the portal for facts to enter. People learn most of what they know about the world through relationships with other people, whether it’s primary caregivers, friends, peers or our social network. And conversation is one of the fundamental ways for people to connect; social change won’t happen without social exchange.

Having said that, I don’t see conversation as a panacea. I believe this requires a three-stage process: 80 per cent education, 15 per cent conversation and five per cent action. A rookie mistake that a lot of organizations make is wanting to jump straight to a solution without going through this process of education and conversation. Albert Einstein once famously said that if he were given one hour to solve the world’s most difficult problem, he would spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and only five minutes on the solution. In line with his wisdom, my book dedicates 10 chapters to the problem and only two chapters to the solution.

There is really no difference between people who are overtly

racist and those who remain silent: The destination is the same.

What are some recommendations for making these conversations truly intentional?

The first thing is, when you’re having a conversation, be focused on the reason you’re having it. Remind everyone that the focus is on the problem at hand and not the characteristics of the people in the room. Also, have a conversation grounded in facts rather than opinions. Feelings and opinions are very important, but conversations have to be informed. You need to have some sort of objective grounding in what you’re doing, which is why I say education, then conversation, then action. But you also have to make room for feelings. It goes back to that primal human connection, and how our mortal fear is being cast out of the group. You need to walk a very delicate tightrope between facts and feelings.

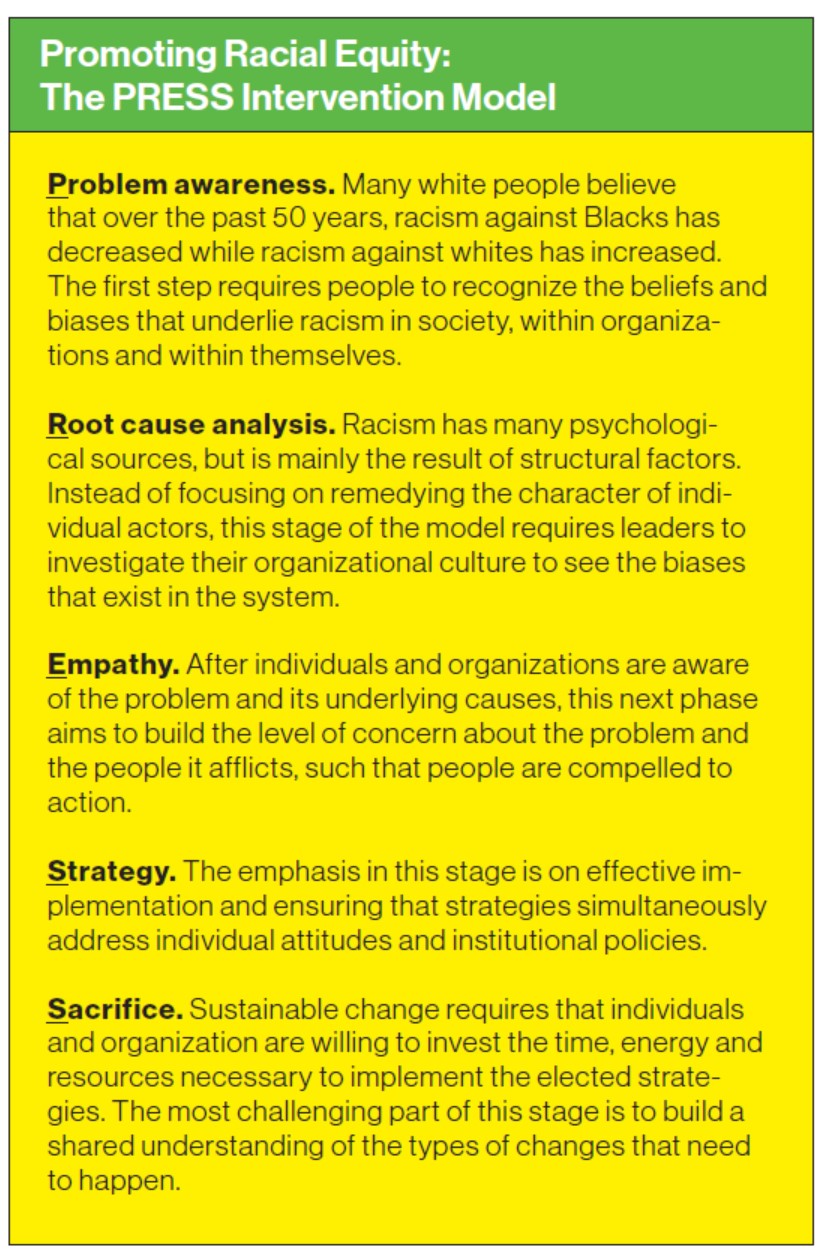

You have developed an intervention model for promoting racial equity in the workplace that you call PRESS. Please describe it.

My model stands for Problem awareness, Root cause analysis, Empathy, Strategy and Sacrifice. Everyone wants to jump to strategies, but strategies are, in some respects, the easiest of those five steps and come later in the process.

To illustrate how this approach works, let’s take a simple example. Say I realize there’s a problem, which is that I gained three pounds. The root cause is Thanksgiving: I ate too much. And do I care? Well, maybe I don’t — it’s just three pounds — but maybe I do because it’s driving up my cholesterol. Then comes the strategy: do I know what to do to lose those three pounds? Well, there’s no shortage of diets and personal trainers. I can give you a long list of tried and true strategies that will actually work, but it all boils down to this: Am I actually willing to do it? Do I care enough to actually do something about it? And doing something about it means sacrifice: Am I willing to invest the time, energy and resources, especially when the going gets rough?

In your book, you share a lot of research showing that many people actually don’t think racism exists.

Many white people still don’t think racism is a real thing, and one reason is that they construe it as ‘evil acts by rotten apples.’ If we just get rid of that one racist cop and people like him, then all of a sudden the Minneapolis Police Department is going to be just fine. It’s easy for people to attribute all the blame to a few bad actors, and fail to understand that racism is systemic.

The term ‘systemic racism’ gets thrown around a lot and is really abstract, so I use a metaphor about salmon to try to explain it. You’ve got a mountain stream that flows downhill because of gravity; that stream has a current, and all the fish that live in the stream are affected by it. If you’re a fish in the stream and you do nothing, the current will push you downstream. If you swim with the current, you’ll go downstream faster. The point is, there is really no difference between people who are overtly racist and those who remain silent and complacent: the destination is the same. You end up where the current takes you. We don’t start off in a neutral world where you do nothing and things stay neutral. You start off in a world that has a current that pushes things in a certain direction.

Anti-racism is about being the salmon that swims against the current and makes it upstream to the pristine headwaters to spawn. It’s a metaphor for producing positive outcomes for the species. But the thing is, it requires a lot of effort, and I know this because I’ve been salmon fishing, and that’s actually what inspired this metaphor. It’s fascinating to watch the salmon’s journey, because it’s really hard, and you see the incredible amount of effort it takes. In fact, only a small percentage of salmon ever make it upstream. You either need to join that group of salmon swimming upstream, or build a dam to stop the current altogether. There needs to be a structural solution for a structural problem.

You sometimes talk about the ‘frozen middle’: The CEO or other executives may have a vision to address racism, but the initiative gets frozen at the middle-management level. What can be done about this?

In the book I talk about three types of people: people who care about promoting opportunity and social justice; people who are apathetic or uninformed and maybe don’t know what to do; and people who are vehemently opposed to it. I call them dolphins, ostriches and sharks, metaphorically speaking. Leaders have to figure out which group they are dealing with and apply differing approaches.

For people who know what to do and are all in (the dolphins) you can just appeal to their ‘better angels’ and give them tools. You basically give them a manual and say, ‘This is what to do.’ They’ll go off and do it because they care about the issue. Then there are the people who are not intrinsically motivated to do the right thing, so you have to give them either carrots or sticks. Some people don’t agree because they’re a bit apathetic, but they’re not really against it, so you can give them a carrot and they’ll come along. But there are other people who say, ‘Over my dead body,’ right? For them, you need sticks.

What managers often fail to do is employ a variety of approaches. They tend to believe that everyone is a good person who cares deeply about social justice. ‘We don’t need carrots or sticks.’ But there’s a lot of data showing that many many people — good people — just don’t care about social justice. They care about their next-door neighbour, and they care about their family, but they just don’t really care about the rest of the world. The data indicate that slightly less than 50 per cent of people are dolphins who champion social justice. Everybody else is either an ostrich or a shark — they don’t care at all, or they are actively committed to dominance, hierarchy and exploitation.

Talk a bit about how individual leaders and colleagues can make a difference.

One thing that makes a big difference at an individual level is whether there’s someone willing to go to bat for you. Many people of colour that I encounter think that their mentor or sponsor has to look like them, but in fact, the research shows that your mentor does not have to look like you. So, if you’re a white executive and you see a person of colour with potential, reach out.

There is also research on confronting racism. If you see a transgression occur, should you speak up? Research shows that when Black or Latinx people speak up, it has the intended effect, but there is a cost to the individual: They are often seen as being a troublemaker. I’m not saying people shouldn’t speak up. I’m just saying — that there’s a cost to doing so, and you have to calculate the trade-off between the cost and the benefit.

White people need to approach this work with a certain amount of humility, because too many come in and want to take over the show. They have a few badges — you know, ‘I voted for Obama, so I can pretty much say or do whatever I want to because I’ve proven that I’m not racist.’

By the way, there is also research behind this: a study found that people who voted for Obama actually do feel like they have ‘moral credentials,’ and that ironically frees them up to be more racist. The bottom line is that a mission statement isn’t enough: the change has to be baked into your policies.

Robert Livingston is a Social Psychologist and Lecturer in Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. He is the author of The Conversation: How Seeking and Speaking the Truth About Racism Can Radically Transform Individuals and Organizations (Currency, 2021.) John J.H. Kim is the founder and CEO of District Management Group (DMGroup), a Senior Lecturer and part of the Social Enterprise Initiative at Harvard Business School. A longer version of this interview was published in the District Management Journal. For more, visit dmgroupk12.com.

Share this article: