Figuring out what consumers truly value these days is no easy feat. Describe how you discovered 30 ‘elements of value’.

Figuring out what consumers truly value these days is no easy feat. Describe how you discovered 30 ‘elements of value’.

My colleagues and I have been studying consumers for many years. After literally hundreds of studies, about three years ago we consolidated our findings and were able to identify 24 ‘elements of value’ — but we suspected there were more. So, in 2015, we did some new qualitative research — talking directly to consumers about the products they were buying.

As people spoke about why they made a particular purchase, we kept asking questions, trying to get at the fundamentals. If someone told us their bank was ‘convenient’, we didn’t accept that answer: We would probe further by asking, ‘What does convenience mean to you?’ The consumer would then delve deeper, and say things like, ‘Well, it’s nearby, so it saves me a lot of time and effort’. We did this repeatedly, across all the different statements consumers made, to get at the most granular elements of value. We ultimately did some quantitative research as well — but it all began with these deep customer insights.

People will give you their money, time and attention in exchange for various types of value.

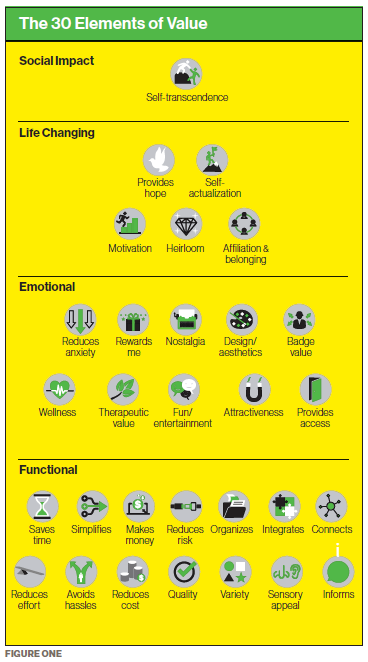

Your 30 building blocks fall into four categories: functional, emotional, life-changing and social impact. How did you arrive at these categories?

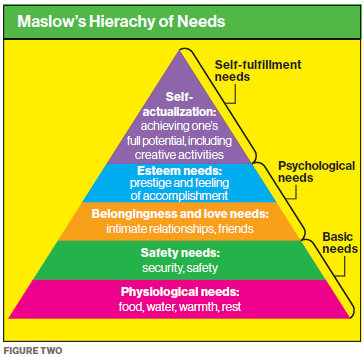

We realized that we couldn’t just provide people with a long list of 30 things to consider; we had to help them mentally organize the elements. At first, we looked at the Periodic Table for inspiration. Then we looked at Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. This well-known ‘pyramid’ of human needs starts out with basic physiological and safety needs. Once these are met, it moves on to psychological needs like belonging, love and feelings of accomplishment. And at the top of the pyramid are self-fulfillment needs, like achieving one’s full potential.

We noticed that these different ‘levels’ of needs could be broken down into several categories: functional needs, emotional needs and transformative needs. And ultimately, at the top of the pyramid, it was clear that some sources of value had to do with different forms of altruism or charity.

When we thought about our 30 elements in the context of Maslow, organizing them into four categories made a lot of sense. By the way, we’re not saying that our hierarchy is complete. It’s really meant to be used as a heuristic concept or guideline; there is room for improvement, and we may discover other elements over time; but in our work with clients, we are finding the model to be quite effective, because it provides a new way to think about value.

You have said that businesses today have to continually look at their products and come up with new ‘combinations of value’. Please explain.

There’s a lot of talk these days about Big Data and the use of advanced analytics to uncover value — and I do believe data plays a role in that. But at the heart of every successful product or service is the concept of value that one is exchanging with the consumer. People will give you their money, time and attention in exchange for various types of value.

I would strongly encourage companies to spend at least as much time thinking about what kind of value they can add as they do thinking about what kind of analytics they can use. My belief is that there is much more economic value to be found by uncovering new forms of value. For example, smartphones are really just bundles of elements of value: you have your friends in your device; you have tools that help you organize your life, like calendars; you have access to your money; you have entertainment, whether it’s video or audio. One of the reasons smartphones have been so successful is that they deliver on multiple elements of value — including functional, emotional and life-changing elements — in a way that is unprecedented in business history. In our work, we’ve been able to quantify that: With the iPhone and iPad, for instance, Apple delivers on 11 of the 30 elements of value. It’s pretty astonishing how they have achieved that.

As indicated, your model traces its roots to psychologist Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Describe how you extended Maslow’s insights.

As indicated, your model traces its roots to psychologist Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Describe how you extended Maslow’s insights.

Whenever I’m giving a talk, I ask the audience if they are familiar with Maslow’s Hierarchy, and just about everyone who works in marketing or strategy raises their hands. It is a very familiar concept; people even say things like, ‘We need to play higher up on the Hierarchy of Needs’. But then I ask a second question: ‘Have you used Maslow’s Hierarchy in a concrete way to help you think about your business?’ Very few hands go up.

In other words, Maslow developed an intriguing theory, but it has remained too academic, and people think it pertains to basic human motivation — as opposed to being directly relevant to business. Our extension of the theory is mostly about making it more practical and applying it to business. Our approach has really resonated with people, because we have made a fundamental psychological theory more appealing to business practitioners.

You have said that the relevance of the 30 elements varies according to industry and demographics. How so?

We did a number of analyses to determine which of the elements was driving an organization’s Net Promoter Score (NPS) — the widely-embraced measure of customer loyalty that Bain’s Fred Reichheld developed 10 years ago. Today, NPS is used by thousands of companies as a simple and effective tracking mechanism for loyalty and advocacy.

In virtually all of the industries where we conducted analyses, quality was the number-one driver of NPS. We believe that likely stems from the Total Quality Movement that started almost 40 years ago. There has been so much improvement in product and service quality in recent decades that if you are not delivering a certain level of perceived quality, you probably can’t make it up with other elements of value. Quality has become almost ‘table stakes’, if you will.

Then, in various industries, things start to diverge. For example, in credit cards, the next element that drives value after quality is rewards me. A lot of credit cards provide rewards, and that is now appearing as a driver of loyalty. Avoids hassles and provides access follow after that. If you compare that with an industry like grocery, after quality, variety is very important, along with sensory appeal, reduces costs and rewards me. So, the drivers do vary by industry.

We’ve looked at demographics in the wireless market in the U.S., studying the entire mobile experience. It turns out that for Baby Boomers, one of the most important elements of value is the connection provided by the wireless network. But if you look at Millennials, they are much more interested in some of the emotional elements of value, such as belonging and entertainment. We are seeing pretty dramatic differences by generation and by industry — and I’m sure it’s even further segmented. As we get larger sample sizes, we’ll be able to look at this in more detail.

Smartphones deliver on multiple elements of value in a way that is unprecedented in business history.

How are companies using the 30 elements in practice?

As indicated, smartphone providers are doing really well — not just Apple. There is something about those devices and the value they offer. Another company that is delivering great value is USAA. We found that their insurance business delivers on 13 of the elements of value. They are known to be a leader in customer satisfaction, but what is interesting is that their service is so good that it’s beginning to ring some of the emotional bells further up the hierarchy, where it’s not just about good functional service anymore. Consumers are feeling an emotional bond with that company.

Describe how tools like ‘structured listening’, ideation sessions and prototyping can be used to embrace the elements of value.

Structured listening is a very active form of listening that involves trying to get below the surface statements that people tend to make. Once you do that kind of listening, you use the findings as stimuli for ‘ideation sessions’. The goal of those sessions is to try to identify where you can add value, or improve upon the value being offered. Companies can focus on improving on the elements of value they currently offer — or they can look at adding new elements to their repertoire.

We typically do several rounds of ideation sessions, using the pyramid with the 30 elements as a stimulus. We ask people, essentially, to think about where they are providing value today, and which elements might be possible for them to provide going forward.

For example, we recently worked with a bank and helped them identify rewards as an element of value that could be important for them. We went on to further explore that concept with their customers, testing ideas of what the rewards could be, and the levels of reward and status, and so forth. Then we developed a prototype that appeared on a smartphone — and showed the different elements of the reward program, etc. We tested that quantitatively with consumers, to optimize the features. Then, it went into market testing and it is just being launched, as we speak. That’s a typical process for us.

Going forward, will you look at how the elements of value contribute to the bottom line?

Yes. We’ve already correlated our findings with both NPS and growth, so we know that companies who are delivering on multiple elements of value tend to grow much more dramatically than those who are not. Next, we will be working on business-to-business elements of value. When companies are selling to other businesses, there may be multiple decision-makers in those businesses, so we’re going to develop a set of elements of value that will show, for example, that what procurement professionals value can be quite different from, say, a business unit head or a project leader.

There has been a resounding outcry for business-to-business elements of value. We started with consumers because they represent roughly 70 per cent of GDP; but business-to-business is also very important. We believe our model for B2B will be nuanced by different types of decision makers, although many of the elements will be the same. I’ll be happy to share our results with your readers when the work is complete.

Eric Almquist is a partner in Bain & Company’s Boston office and leader of Bain’s global Customer Insights and Analytics capability. Prior to joining Bain, he spent 24 years with Mercer Management Consulting (now Oliver Wyman).